Years ago if you saw a photo of a polar bear, the background would almost certainly have been white ice or snow. Pictures like this have become commonplace as some scientists have sought to highlight & dramatise the changing Arctic climate.

For penguins the effects of ice melting in Antarctica are more mixed. Earlier springs mean earlier breeding and more penguins but the increased penguin population is having to swim further to catch fish which are moving to seek colder water.

Rising temperatures may lead to phenomena like algae infesting melting glaciers, as shown here with the Canada Glacier in Antarctica, or bleached coral. Bleaching does not actually kill coral but it does lower its resistance to disease.

The solitary figure in the landscape is in Barrow, Alaska, the northernmost US town, 539kms above the Arctic Circle, where the c. 1,800 residents, mostly Eskimos or Inuit, see no sun from late November to January. The pictured Inuit is from Baffin Island, Canada. Such people are finding food with increasing difficulty because caribou, for example, their staple diet, are falling through the thinning ice cap.

The problem is not confined to polar regions, although they are experiencing the most rapid warming. The picture shows Male, capital of the Maldive Islands in the Indian Ocean. With a maximum elevation of 2.4 metres, the inhabitants have erected a sea wall as protection against a possible rise in sea level.

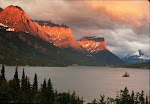

St Mary's Lake in Montana's Glacier National Park. In 1910 there were 150 glaciers; now there are 30.

Damage caused by Hurricane Ivan in Breeze Point, Florida, 2004. Of course, hurricanes happened before global warming and the tendency to blame all natural disasters, such as the 2005 tsunami, on climaate change are ludicrous.

The greatest natural diasaster of modern times was Krakatoa erupting in 1883, long before anyone dreamt of global warming..

Thursday, May 28, 2009

Monday, May 25, 2009

Monday, May 11, 2009

Problem & solution

Problem & solution

Global warming is widely perceived today, worldwide, as a major problem facing mankind. Simply defined, it is the heating up of the earth's atmosphere due to higher greenhouse gas emissions. The fear is that increased temperatures will lead to melting polar ice-caps, rising sea levels, which could cause flooding affecting millions in densely-poulated low-lying areas of the world, and an increase in the occurrence of natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina.

The film , An Inconvenient Truth. directed by Davis Guggenheim, 2006, presented by Al Gore, dramatically highlights the dangers involved. We watched the movie and read reviews of it, mostly favourable, e.g. Brandon Fibbs, but some critical, e.g. Scott & Eric. The film was very well presented, with lots of statistical information, graphs and charts as well as some very dramatic photographic evidence. In addition we measured our carbon foorprints & mine was 4.1.

The class average for CRC was 3.86.

All this is food for thought, but I have some reservations I don't consider myself to be an extravagant consumer of food or energy & I don't see how becoming vegetarian or vegan will save the planet, yet that was the implicit assumption in some of the questions we answered to obtain our footprint. In addition, how can we find a solution if not everyone agrees about the scope of the problem? Nicholas Stern, in A Blueprint for a Safer Planet, has suggested that controlling global C02 emissions is desirable, achievable & affordable, but Nigel Lawson, in A Load of Hot Air, has refuted this:

'The Stern Review sought to argue that atmospheric greenhouse gas (chiefly carbon dioxide) concentrations could be stabilised at relatively low global cost, and the resulting benefit from preventing much further warming would far outweigh that cost. This analysis has been wholly discredited by pretty well every prominent economist who has addressed the issue. '

If there is no widespread agreement as to the scope of the problem, and the costs involved in dealing with it, then we have a long way to go before we find a solution.

Bibliography:

An Inconvenient Truth. Dir. Davis Guggenheim. Perf. Al Gore. DVD. Paramount Classics, 2006

Lawson, Nigel. "A Load of Hot Air." Rev. of A Blueprint for a Safer Planet: How to Manage Climate Change & Create a new Era of Progress & Prosperity, by Nicholas Stern, Bodley Head, 2009. The Spectator 29 Apr. 2009.

Brandon Fibbs, http://brandonfibbs.com/2006/05/24/an-inconvenient-truth/

Scott & Eric http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/inconvenient_truth/articles/156,

http://footprint.wwf.org.uk/

Global warming is widely perceived today, worldwide, as a major problem facing mankind. Simply defined, it is the heating up of the earth's atmosphere due to higher greenhouse gas emissions. The fear is that increased temperatures will lead to melting polar ice-caps, rising sea levels, which could cause flooding affecting millions in densely-poulated low-lying areas of the world, and an increase in the occurrence of natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina.

The film , An Inconvenient Truth. directed by Davis Guggenheim, 2006, presented by Al Gore, dramatically highlights the dangers involved. We watched the movie and read reviews of it, mostly favourable, e.g. Brandon Fibbs, but some critical, e.g. Scott & Eric. The film was very well presented, with lots of statistical information, graphs and charts as well as some very dramatic photographic evidence. In addition we measured our carbon foorprints & mine was 4.1.

The class average for CRC was 3.86.

All this is food for thought, but I have some reservations I don't consider myself to be an extravagant consumer of food or energy & I don't see how becoming vegetarian or vegan will save the planet, yet that was the implicit assumption in some of the questions we answered to obtain our footprint. In addition, how can we find a solution if not everyone agrees about the scope of the problem? Nicholas Stern, in A Blueprint for a Safer Planet, has suggested that controlling global C02 emissions is desirable, achievable & affordable, but Nigel Lawson, in A Load of Hot Air, has refuted this:

'The Stern Review sought to argue that atmospheric greenhouse gas (chiefly carbon dioxide) concentrations could be stabilised at relatively low global cost, and the resulting benefit from preventing much further warming would far outweigh that cost. This analysis has been wholly discredited by pretty well every prominent economist who has addressed the issue. '

If there is no widespread agreement as to the scope of the problem, and the costs involved in dealing with it, then we have a long way to go before we find a solution.

Bibliography:

An Inconvenient Truth. Dir. Davis Guggenheim. Perf. Al Gore. DVD. Paramount Classics, 2006

Lawson, Nigel. "A Load of Hot Air." Rev. of A Blueprint for a Safer Planet: How to Manage Climate Change & Create a new Era of Progress & Prosperity, by Nicholas Stern, Bodley Head, 2009. The Spectator 29 Apr. 2009.

Brandon Fibbs, http://brandonfibbs.com/2006/05/24/an-inconvenient-truth/

Scott & Eric http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/inconvenient_truth/articles/156,

http://footprint.wwf.org.uk/

Monday, May 4, 2009

Cool City

We watched the Cool City video.

According to the video:

Economic development since the Industrial Revolution has been breathtaking but it has brought with it problems such as population pressure & CO2 emissions.

If we don't act to solve these problems, we'll need another earth, clearly impossible.

We have to reduce CO2 emissions by 50%.

In Japan during the last 30 years, GDP has doubled, while energy efficiency has increased by 37% & oil consumption decreased by 8%.

90% of CO2 emitted into the air comes from buildings & transport.

Cool city is an environmentally friendly green city with minimal CO2 emissions.

It is being built by SDCJ, a group of Japanese companies.

There are 3 main zones: Business; Commercial/Cultural; Residential.

Three types of transport mentioned were light transit rail/monorail; solar water taxis; hybrid cars.

Heat-reducing techniques: tree-planting; waterways; rooftop membranes.

Expected CO2 reductions: for eco-towers 50% & for eco-residences 30%.

Overall reduction of CO2 emissions is expected to be 60%.

How practical/ realistic is the video?

It certainly looks good but I'm personally sceptical as to what % of the Emirates' population will ever live in such a cool city.

It will involve a massive shift in lifestyle & cultural attitudes.

For a corrective viewpoint, see the posting below, A Load of Hot Air.

215 words

According to the video:

Economic development since the Industrial Revolution has been breathtaking but it has brought with it problems such as population pressure & CO2 emissions.

If we don't act to solve these problems, we'll need another earth, clearly impossible.

We have to reduce CO2 emissions by 50%.

In Japan during the last 30 years, GDP has doubled, while energy efficiency has increased by 37% & oil consumption decreased by 8%.

90% of CO2 emitted into the air comes from buildings & transport.

Cool city is an environmentally friendly green city with minimal CO2 emissions.

It is being built by SDCJ, a group of Japanese companies.

There are 3 main zones: Business; Commercial/Cultural; Residential.

Three types of transport mentioned were light transit rail/monorail; solar water taxis; hybrid cars.

Heat-reducing techniques: tree-planting; waterways; rooftop membranes.

Expected CO2 reductions: for eco-towers 50% & for eco-residences 30%.

Overall reduction of CO2 emissions is expected to be 60%.

How practical/ realistic is the video?

It certainly looks good but I'm personally sceptical as to what % of the Emirates' population will ever live in such a cool city.

It will involve a massive shift in lifestyle & cultural attitudes.

For a corrective viewpoint, see the posting below, A Load of Hot Air.

215 words

A load of hot air

A load of hot air

Wednesday, 29th April 2009

A Blueprint for a Safer Planet: How to Manage Climate Change and Create a new Era of Progress and Prosperity

Nicholas Stern Bodley Head, 246pp, £16.99

As a general rule, I do not believe in reviewing bad books. Review space is limited, and the many good books that are published deserve first claim on it. But climate change is such an important subject, and — thanks to heavy promotion by that great publicist, Tony Blair — the Stern Review of the economics of climate change has become so well known (not least to the vast majority who have never read it, among whom in all probability is Mr Blair), that anything from Lord Stern deserves some attention.

However, anyone looking for anything new in this rather arrogant book — all those who dissent from Stern’s analysis, his predictions, or his prescriptions are dismissed as ‘both ignorant and reckless’ (the word ‘ignorant’ recurs frequently) — will be disappointed. The first half of the book is a rehash of the original Stern Review, and the second half a rehash of his lengthy 2008 LSE study Key Elements of a Global Deal on Climate Change. This last is an exercise in political naivety which does not improve on its second outing; and the European Union leadership trumpeted by Stern (‘We can expect the EU and its member countries to continue to drive forward action on climate change’) has already collapsed with the back-tracking at the EU climate summit last December, after this book went to press.

The Stern Review sought to argue that atmospheric greenhouse gas (chiefly carbon dioxide) concentrations could be stabilised at relatively low global cost, and the resulting benefit from preventing much further warming would far outweigh that cost. This analysis has been wholly discredited by pretty well every prominent economist who has addressed the issue. For example, Professor Helm of Oxford, probably Britain’s most eminent energy economist, has recently observed that Stern’s implausibly low ‘cost numbers … [are] all but useless for the purposes of policy design and implementation’. So far from seriously addressing the substantial objections Stern’s critics have made, this book essentially just reiterates the original (non-peer reviewed, incidentally) analysis.

The only significant economic support for Stern’s prescription has come from Professor Weitzman, of Harvard, who accepts that Stern’s cost-benefit analysis is all wrong, but maintains that this is an issue where cost benefit analysis is inapplicable: there is an outside chance of a disaster so great that it needs to be averted irrespective of cost. One obvious problem with this approach, however, is that there is an outside chance of all manner of disasters, and we cannot spend unlimited resources on seeking to avert them all. Moreover, one of them is a new ice age, which would be very much worse; and indeed the formidably eminent scientist, Professor Freeman Dyson of Princeton, believes that any warming that might occur might well be helpful in forestalling a new ice age.

Not that there has been any global warming lately. The recorded global temperature trend so far this century (2001-2008 inclusive) has been completely flat, despite the predicted warming of all the computer models in which Stern places uncritical faith and despite (until the onset of the current world recession) a much faster than predicted growth in carbon emissions. This unexpected development, which at the very least demonstrates that the whole issue is both more complex and less certain than he would have us believe, is blithely ignored by Stern, who assures us that ‘the [temperature] trend is clearly upwards’, and that ‘rapid climate change’ is on the way — although he subsequently defines ‘rapid’ as ‘within the next century or two’. His ability to foretell the distant future is remarkable.

But then respect for the evidence is not a strong point of this book. To take just one example (and there are many), as part of his alarmist narrative he tells us that ‘low-lying island states such as Tuvalu are submerging’. This canard, which I believe was first launched by the climate change propagandist Al Gore, is wholly unfounded. In 1993, scientists from Flinders University in Australia, believing that the old float-type tide gauges used in the South Pacific (which were registering an annual sea-level rise of a negligible 0.7 millimetres a year) must be inaccurate, placed new modern ones around a dozen Pacific islands, including Tuvalu. After more than a decade of finding no sign of any significant sea-level rise (in 2006 Tuvalu actually recorded a fall) the project was abandoned.

Clearly concerned that there is still less than total acceptance of his message, Stern warmly commends direct action by Greenpeace and the like, and warns, mafia style, that ‘there are fewer and fewer hiding places for firms wanting to conceal dubious, unsafe or irresponsible practices’. Even the media are blamed for giving ‘similar time to scientists and deniers of the science, when the balance of argument in logic and evidence is 99 (or more) to 1, not 50-50’.

In fact, the media give far from equal time to the two sides in this debate. As I know from my own experience, it is virtually impossible for a dissenting voice to be given a hearing on any flagship BBC programme, either on radio or on television. But what is truly mind-boggling is Stern’s assertion, without adducing a scrap of supporting evidence, that informed opinion is 99 per cent (or more) on his side.

The most thorough survey of the views of climate scientists was conducted by Dr Dennis Bray, a social scientist, and Professor Hans von Storch of the Meteorological Institute at Hamburg University, and published in 2007. Asked whether they agreed with the proposition that ‘climate change is mostly the result of anthropogenic [ie man-made] causes’, 66 per cent agreed, of whom 38 per cent ‘strongly agreed’. In other words, a majority well short of Stern’s 99 per cent agreed, and only a minority ‘strongly agreed’.

Moreover, when they were asked what they felt to be ‘the most pressing issue facing humanity today’, which Stern asserts is climate change caused by global warming, only 8 per cent of them placed this first. So it would be closer to the truth to say that probably at least 90 per cent of informed opinion disagrees, one way or another, with Stern’s crude alarmism. If there is one silver lining to the current world recession, it is that it might bring about a dose of realism which will help us to escape from the highly damaging global warming madness which this book epitomises.

Nigel Lawson’s book, An Appeal to Reason: A Cool Look at Global Warming, is now available, with a new afterword, in paperback (Duckworth Overlook, £6.99).

Wednesday, 29th April 2009

A Blueprint for a Safer Planet: How to Manage Climate Change and Create a new Era of Progress and Prosperity

Nicholas Stern Bodley Head, 246pp, £16.99

As a general rule, I do not believe in reviewing bad books. Review space is limited, and the many good books that are published deserve first claim on it. But climate change is such an important subject, and — thanks to heavy promotion by that great publicist, Tony Blair — the Stern Review of the economics of climate change has become so well known (not least to the vast majority who have never read it, among whom in all probability is Mr Blair), that anything from Lord Stern deserves some attention.

However, anyone looking for anything new in this rather arrogant book — all those who dissent from Stern’s analysis, his predictions, or his prescriptions are dismissed as ‘both ignorant and reckless’ (the word ‘ignorant’ recurs frequently) — will be disappointed. The first half of the book is a rehash of the original Stern Review, and the second half a rehash of his lengthy 2008 LSE study Key Elements of a Global Deal on Climate Change. This last is an exercise in political naivety which does not improve on its second outing; and the European Union leadership trumpeted by Stern (‘We can expect the EU and its member countries to continue to drive forward action on climate change’) has already collapsed with the back-tracking at the EU climate summit last December, after this book went to press.

The Stern Review sought to argue that atmospheric greenhouse gas (chiefly carbon dioxide) concentrations could be stabilised at relatively low global cost, and the resulting benefit from preventing much further warming would far outweigh that cost. This analysis has been wholly discredited by pretty well every prominent economist who has addressed the issue. For example, Professor Helm of Oxford, probably Britain’s most eminent energy economist, has recently observed that Stern’s implausibly low ‘cost numbers … [are] all but useless for the purposes of policy design and implementation’. So far from seriously addressing the substantial objections Stern’s critics have made, this book essentially just reiterates the original (non-peer reviewed, incidentally) analysis.

The only significant economic support for Stern’s prescription has come from Professor Weitzman, of Harvard, who accepts that Stern’s cost-benefit analysis is all wrong, but maintains that this is an issue where cost benefit analysis is inapplicable: there is an outside chance of a disaster so great that it needs to be averted irrespective of cost. One obvious problem with this approach, however, is that there is an outside chance of all manner of disasters, and we cannot spend unlimited resources on seeking to avert them all. Moreover, one of them is a new ice age, which would be very much worse; and indeed the formidably eminent scientist, Professor Freeman Dyson of Princeton, believes that any warming that might occur might well be helpful in forestalling a new ice age.

Not that there has been any global warming lately. The recorded global temperature trend so far this century (2001-2008 inclusive) has been completely flat, despite the predicted warming of all the computer models in which Stern places uncritical faith and despite (until the onset of the current world recession) a much faster than predicted growth in carbon emissions. This unexpected development, which at the very least demonstrates that the whole issue is both more complex and less certain than he would have us believe, is blithely ignored by Stern, who assures us that ‘the [temperature] trend is clearly upwards’, and that ‘rapid climate change’ is on the way — although he subsequently defines ‘rapid’ as ‘within the next century or two’. His ability to foretell the distant future is remarkable.

But then respect for the evidence is not a strong point of this book. To take just one example (and there are many), as part of his alarmist narrative he tells us that ‘low-lying island states such as Tuvalu are submerging’. This canard, which I believe was first launched by the climate change propagandist Al Gore, is wholly unfounded. In 1993, scientists from Flinders University in Australia, believing that the old float-type tide gauges used in the South Pacific (which were registering an annual sea-level rise of a negligible 0.7 millimetres a year) must be inaccurate, placed new modern ones around a dozen Pacific islands, including Tuvalu. After more than a decade of finding no sign of any significant sea-level rise (in 2006 Tuvalu actually recorded a fall) the project was abandoned.

Clearly concerned that there is still less than total acceptance of his message, Stern warmly commends direct action by Greenpeace and the like, and warns, mafia style, that ‘there are fewer and fewer hiding places for firms wanting to conceal dubious, unsafe or irresponsible practices’. Even the media are blamed for giving ‘similar time to scientists and deniers of the science, when the balance of argument in logic and evidence is 99 (or more) to 1, not 50-50’.

In fact, the media give far from equal time to the two sides in this debate. As I know from my own experience, it is virtually impossible for a dissenting voice to be given a hearing on any flagship BBC programme, either on radio or on television. But what is truly mind-boggling is Stern’s assertion, without adducing a scrap of supporting evidence, that informed opinion is 99 per cent (or more) on his side.

The most thorough survey of the views of climate scientists was conducted by Dr Dennis Bray, a social scientist, and Professor Hans von Storch of the Meteorological Institute at Hamburg University, and published in 2007. Asked whether they agreed with the proposition that ‘climate change is mostly the result of anthropogenic [ie man-made] causes’, 66 per cent agreed, of whom 38 per cent ‘strongly agreed’. In other words, a majority well short of Stern’s 99 per cent agreed, and only a minority ‘strongly agreed’.

Moreover, when they were asked what they felt to be ‘the most pressing issue facing humanity today’, which Stern asserts is climate change caused by global warming, only 8 per cent of them placed this first. So it would be closer to the truth to say that probably at least 90 per cent of informed opinion disagrees, one way or another, with Stern’s crude alarmism. If there is one silver lining to the current world recession, it is that it might bring about a dose of realism which will help us to escape from the highly damaging global warming madness which this book epitomises.

Nigel Lawson’s book, An Appeal to Reason: A Cool Look at Global Warming, is now available, with a new afterword, in paperback (Duckworth Overlook, £6.99).

Thursday, April 30, 2009

Are electric cars really the next big step for mankind?

ELISABETH JEFFRIES

The Spectator

WEDNESDAY, 29th APRIL 2009

If internal combustion is going to be superceded by battery power, says Elisabeth Jeffries, carmakers and governments need to invest on a scale akin to the Apollo space programme.

Putting Lord Mandelson into an electric Mini may not seem to bear much comparison with putting a man on the moon, but there are interesting parallels.

In 1961, the US government embarked on the Apollo space programme, with the ambition of landing astronauts on the moon by the end of the decade. By 1969, it had achieved exactly what it set out to do. But it was a risky project, with no guarantee of success. To land on the moon, scientists had to solve three problems: how to rendezvous and dock with another spacecraft, how to work outside a spacecraft, and how to survive prolonged periods of time in space. In total, the US government spent $20 billion on the project (about $350 billion in today’s money), driven by a desire to upstage and defeat the menace of the age — the Soviet Union.

That world has gone. A new perceived menace has emerged, greenhouse gas, and a new programme is creaking into gear to control it: low-carbon technology. Today’s challenge is to produce an electric car that can travel 200 miles without recharging its battery: a cinch compared to space travel, you might have thought.

Yet governments and vehicle producers are groping in the dark. Back in the 1920s, electric cars briefly commanded a 20 per cent share of the motor vehicle market, but the technology was sidelined as oil supplies became increasingly abundant and manufacturers concentrated on the carbon-fuelled internal combustion (IC) engine. An electric car launched by General Motors in the 1990s was quietly snuffed.

GM had gradually overtaken Ford and become the world’s most successful car producer, but its fortunes were on a long downward slide towards the brink of bankruptcy it faces today. After decades of consolidation across the industry, only a handful of global manufacturers remain, and far too many conventional vehicles are being produced.

Enter the green car. First there was the Toyota hybrid (a petrol-driven vehicle that can use electricity at low speeds). Next is GM’s Chevrolet Volt — due to be launched in the US next year — similar to GM’s Vauxhall Ampera in the UK, the prototype of which was unveiled at the Geneva motor show in March. For trips of up to 37 miles, the Ampera will run only on a lithium ion battery, more commonly used in laptop computers; for longer journeys, it will continue to use electricity, but generated by a small internal combustion engine.

And earlier this year an electric car in a different class altogether was unveiled — the Tesla Roadster, a California sports car that can go 220 miles without recharging, costs E112,000 in Europe, and was hailed by Boris Johnson under the Daily Telegraph headline ‘How to drive fast, have a good time — and still save the planet’.

The puzzle is why the hybrid electric car should be the next big thing, as competing announcements by car manufacturers suggest. It is pricier to develop than more efficient versions of conventional cars or new models using current electric-power technology. But, as Dr Paul Nieuwenhuis of the Centre for Automotive Industry Research at Cardiff University indicates, ‘The industry has hit a brick wall. To become more profitable, in the longer term it would have to change the way it approaches manufacturing and distribution’ — for example by using a greater number of smaller local plants and cutting out the dealers, an unlikely scenario.

Instead, the industry is locked into competing on the ‘power train’ — the parts that drive the car forward — and producing IC engines differentiated according to model or manufacturer. This means their factories are built along a particular format that is expensive to re-engineer for ‘pure’ electric cars. ‘That’s why the industry loves the hybrid,’ says Nieuwenhuis.

GM wants a new hook to compete on, and seems serious about hybrids. ‘This is the start of where we’re going. The way the system is designed it doesn’t have to have an IC alongside it, but there’s the flexibility of having the IC if you need it... we’re already in an advanced stage of development,’ says GM spokesman Craig Cheetham, who predicts that 4,000-5,000 Amperas will be sold in the UK in 2012 — about 1.5 per cent of GM’s UK sales. After that, he says, GM will take the power system and make it available for other models. The mouth-watering improvement in sales and image experienced by Toyota after the launch of the hybrid Prius is the most likely spur to GM’s enthusiasm.

GM says it will make its own battery pack for the Ampera at existing facilities neighbouring its Ellesmere Port plant, if the car is manufactured in the UK. But producers are still some way off solving battery performance, an essential requirement if hybrid and electric cars are to become widespread, allowing customers to feel confident that they can set off on a journey without running out of juice. Batteries still do not last long enough. To achieve its range, the Tesla has to carry thousands of lithium ion battery cells — one reason for its high price.

According to Nieuwenhuis, the main cost of a typical hybrid car is in its battery, amounting to around £15,000 at present — the same cost as producing the rest of the car. Improving the battery and bringing down the cost will take a decade, he thinks. ‘It is probably reasonable to assume that by 2020, battery costs will have halved as a result of mass production — which will begin for plug-in hybrids, but pure battery-electric vehicles will also benefit.’

So the plug-in hybrid (so called because it recharges at the mains), starting off as a lossmaker, could be fully functional and competitive within 11 years — a similar time span as the Apollo moonshot programme.

But there are major snags. GM and other mass carmakers are in deep trouble, pleading for bail-outs and more ‘scrappage’ schemes like the one introduced in last month’s Budget to encourage new car buyers. ‘Production of the Ampera is definitely going ahead regardless. What we are campaigning for is not government funding per se, but a government incentive to encourage customers to adopt the new technology,’ claims Cheetham. The recent photo-opportunity which put the Business Secretary Lord Mandelson and the Transport Secretary Geoff Hoon into an electric Mini on a Scottish race circuit was a partial response, announcing subsidies of up to £5,000 for buyers of electric cars from 2011. But no government has so far committed really big money for this endeavour.

Global government stimuli allocated for low-carbon vehicles have so far amounted to $15.9 billion, according to a study by HSBC. Most of that has been allocated to R&D for developing lighter batteries and plug-in hybrids, as well as tax credits or rebates for customers buying new, low-emitting vehicles. But more is needed. According to Lew Fulton, an expert at the International Energy Agency, plug-in hybrids may eventually cost about $5,000 more than conventional models, so putting two million plug-in hybrids on the road annually by 2020 could cost an additional $10 billion a year. Continuing research into battery and pure electric vehicle development generally could add another $1 billion a year, he suggests.

The total bill will run into hundreds of billions over the next two decades — more than the moon landings in real terms — if plug-in hybrids and electric vehicles are to become commonplace. And there will be much more existing clutter to clear away; for instance, a network of plug-in or battery-pack replacement points for cars needs to be set up in parallel with petrol stations. The widespread use of electric cars probably also involves adding to electricity generating capacity — though of course it also reduces demand for petrol distribution.

The auto industry can take electric cars in two directions. Nieuwenhuis suggests it can create a high-value market for them: ‘Historically, battery electric vehicles are usually sold to well-to-do ladies in urban areas who use them to do a bit of shopping, do lunch, visit friends. If such niches can be identified, there is a future for electric vehicles even with their existing limited range — as long as we don’t expect them to do the same things as our internal-combustion cars,’ he says.

Alternatively, it can try to sell them more widely and ramp up performance. Today’s governments should read the history of the Apollo programme: find a vision, set a deadline, put your money where your mouth is. But make no mistake, launching the age of the electric car will be tougher than going to the moon.

The Spectator

WEDNESDAY, 29th APRIL 2009

If internal combustion is going to be superceded by battery power, says Elisabeth Jeffries, carmakers and governments need to invest on a scale akin to the Apollo space programme.

Putting Lord Mandelson into an electric Mini may not seem to bear much comparison with putting a man on the moon, but there are interesting parallels.

In 1961, the US government embarked on the Apollo space programme, with the ambition of landing astronauts on the moon by the end of the decade. By 1969, it had achieved exactly what it set out to do. But it was a risky project, with no guarantee of success. To land on the moon, scientists had to solve three problems: how to rendezvous and dock with another spacecraft, how to work outside a spacecraft, and how to survive prolonged periods of time in space. In total, the US government spent $20 billion on the project (about $350 billion in today’s money), driven by a desire to upstage and defeat the menace of the age — the Soviet Union.

That world has gone. A new perceived menace has emerged, greenhouse gas, and a new programme is creaking into gear to control it: low-carbon technology. Today’s challenge is to produce an electric car that can travel 200 miles without recharging its battery: a cinch compared to space travel, you might have thought.

Yet governments and vehicle producers are groping in the dark. Back in the 1920s, electric cars briefly commanded a 20 per cent share of the motor vehicle market, but the technology was sidelined as oil supplies became increasingly abundant and manufacturers concentrated on the carbon-fuelled internal combustion (IC) engine. An electric car launched by General Motors in the 1990s was quietly snuffed.

GM had gradually overtaken Ford and become the world’s most successful car producer, but its fortunes were on a long downward slide towards the brink of bankruptcy it faces today. After decades of consolidation across the industry, only a handful of global manufacturers remain, and far too many conventional vehicles are being produced.

Enter the green car. First there was the Toyota hybrid (a petrol-driven vehicle that can use electricity at low speeds). Next is GM’s Chevrolet Volt — due to be launched in the US next year — similar to GM’s Vauxhall Ampera in the UK, the prototype of which was unveiled at the Geneva motor show in March. For trips of up to 37 miles, the Ampera will run only on a lithium ion battery, more commonly used in laptop computers; for longer journeys, it will continue to use electricity, but generated by a small internal combustion engine.

And earlier this year an electric car in a different class altogether was unveiled — the Tesla Roadster, a California sports car that can go 220 miles without recharging, costs E112,000 in Europe, and was hailed by Boris Johnson under the Daily Telegraph headline ‘How to drive fast, have a good time — and still save the planet’.

The puzzle is why the hybrid electric car should be the next big thing, as competing announcements by car manufacturers suggest. It is pricier to develop than more efficient versions of conventional cars or new models using current electric-power technology. But, as Dr Paul Nieuwenhuis of the Centre for Automotive Industry Research at Cardiff University indicates, ‘The industry has hit a brick wall. To become more profitable, in the longer term it would have to change the way it approaches manufacturing and distribution’ — for example by using a greater number of smaller local plants and cutting out the dealers, an unlikely scenario.

Instead, the industry is locked into competing on the ‘power train’ — the parts that drive the car forward — and producing IC engines differentiated according to model or manufacturer. This means their factories are built along a particular format that is expensive to re-engineer for ‘pure’ electric cars. ‘That’s why the industry loves the hybrid,’ says Nieuwenhuis.

GM wants a new hook to compete on, and seems serious about hybrids. ‘This is the start of where we’re going. The way the system is designed it doesn’t have to have an IC alongside it, but there’s the flexibility of having the IC if you need it... we’re already in an advanced stage of development,’ says GM spokesman Craig Cheetham, who predicts that 4,000-5,000 Amperas will be sold in the UK in 2012 — about 1.5 per cent of GM’s UK sales. After that, he says, GM will take the power system and make it available for other models. The mouth-watering improvement in sales and image experienced by Toyota after the launch of the hybrid Prius is the most likely spur to GM’s enthusiasm.

GM says it will make its own battery pack for the Ampera at existing facilities neighbouring its Ellesmere Port plant, if the car is manufactured in the UK. But producers are still some way off solving battery performance, an essential requirement if hybrid and electric cars are to become widespread, allowing customers to feel confident that they can set off on a journey without running out of juice. Batteries still do not last long enough. To achieve its range, the Tesla has to carry thousands of lithium ion battery cells — one reason for its high price.

According to Nieuwenhuis, the main cost of a typical hybrid car is in its battery, amounting to around £15,000 at present — the same cost as producing the rest of the car. Improving the battery and bringing down the cost will take a decade, he thinks. ‘It is probably reasonable to assume that by 2020, battery costs will have halved as a result of mass production — which will begin for plug-in hybrids, but pure battery-electric vehicles will also benefit.’

So the plug-in hybrid (so called because it recharges at the mains), starting off as a lossmaker, could be fully functional and competitive within 11 years — a similar time span as the Apollo moonshot programme.

But there are major snags. GM and other mass carmakers are in deep trouble, pleading for bail-outs and more ‘scrappage’ schemes like the one introduced in last month’s Budget to encourage new car buyers. ‘Production of the Ampera is definitely going ahead regardless. What we are campaigning for is not government funding per se, but a government incentive to encourage customers to adopt the new technology,’ claims Cheetham. The recent photo-opportunity which put the Business Secretary Lord Mandelson and the Transport Secretary Geoff Hoon into an electric Mini on a Scottish race circuit was a partial response, announcing subsidies of up to £5,000 for buyers of electric cars from 2011. But no government has so far committed really big money for this endeavour.

Global government stimuli allocated for low-carbon vehicles have so far amounted to $15.9 billion, according to a study by HSBC. Most of that has been allocated to R&D for developing lighter batteries and plug-in hybrids, as well as tax credits or rebates for customers buying new, low-emitting vehicles. But more is needed. According to Lew Fulton, an expert at the International Energy Agency, plug-in hybrids may eventually cost about $5,000 more than conventional models, so putting two million plug-in hybrids on the road annually by 2020 could cost an additional $10 billion a year. Continuing research into battery and pure electric vehicle development generally could add another $1 billion a year, he suggests.

The total bill will run into hundreds of billions over the next two decades — more than the moon landings in real terms — if plug-in hybrids and electric vehicles are to become commonplace. And there will be much more existing clutter to clear away; for instance, a network of plug-in or battery-pack replacement points for cars needs to be set up in parallel with petrol stations. The widespread use of electric cars probably also involves adding to electricity generating capacity — though of course it also reduces demand for petrol distribution.

The auto industry can take electric cars in two directions. Nieuwenhuis suggests it can create a high-value market for them: ‘Historically, battery electric vehicles are usually sold to well-to-do ladies in urban areas who use them to do a bit of shopping, do lunch, visit friends. If such niches can be identified, there is a future for electric vehicles even with their existing limited range — as long as we don’t expect them to do the same things as our internal-combustion cars,’ he says.

Alternatively, it can try to sell them more widely and ramp up performance. Today’s governments should read the history of the Apollo programme: find a vision, set a deadline, put your money where your mouth is. But make no mistake, launching the age of the electric car will be tougher than going to the moon.

Monday, April 27, 2009

Traditions weigh heavy on China's women, BBC June 19th 2006

Summary:

In this article, Christopher Allen examines the suicide rate in China, where 1.5M women attempt suicide every year, 10% succeeding, according to WHO figures. The problem is worse in rural areas, where poisonous pesticides are more readily available. Some suicides are impulsive but many are due to traditional arranged marriages. Bought brides leave their own homes to enter an alien environment, where resentment can often lead to violence, and where the young wife is isolated. In rural areas particularly, wives are expected to play a subservient role. Furthermore, sons are preferred to daughters and widespread abortion of female foetuses means more boys than girls are born which could lead to a serious shortage of women in the future. There are fears this will lead to more female trafficking, prostitution, sexual violence & rape.

The Government has passed laws banning arranged marriages but traditional attitudes are hard to change. The Suicide Prevention Project at the Beijing Cultural Development Centre is attempting to help rural women by establishing village-based support groups. Early signs are encouraging and there are hopes of a national network

Young women in cities often face poor working conditions & sexual harassment but there are signs that, gaining in experience, such women are becoming more independent & confident than their rural counterparts.

206 words

Main idea:

Chinese women in rural areas, forced by tradition into arranged marriages where they are expected to be totally subservient, are seeking escape through suicide. Young women in urban areas face difficulties too but seem to be gaining more in confidence & self-reliance.

Comment:

I feel that this is an important topic and highly relevant to those of us who work here in the Middle East, where arranged marriages are also the norm. It will be interesting to see to what extent, if any, attitudes change in China and whether such change, if it comes, will be reflected here in the Gulf.

In this article, Christopher Allen examines the suicide rate in China, where 1.5M women attempt suicide every year, 10% succeeding, according to WHO figures. The problem is worse in rural areas, where poisonous pesticides are more readily available. Some suicides are impulsive but many are due to traditional arranged marriages. Bought brides leave their own homes to enter an alien environment, where resentment can often lead to violence, and where the young wife is isolated. In rural areas particularly, wives are expected to play a subservient role. Furthermore, sons are preferred to daughters and widespread abortion of female foetuses means more boys than girls are born which could lead to a serious shortage of women in the future. There are fears this will lead to more female trafficking, prostitution, sexual violence & rape.

The Government has passed laws banning arranged marriages but traditional attitudes are hard to change. The Suicide Prevention Project at the Beijing Cultural Development Centre is attempting to help rural women by establishing village-based support groups. Early signs are encouraging and there are hopes of a national network

Young women in cities often face poor working conditions & sexual harassment but there are signs that, gaining in experience, such women are becoming more independent & confident than their rural counterparts.

206 words

Main idea:

Chinese women in rural areas, forced by tradition into arranged marriages where they are expected to be totally subservient, are seeking escape through suicide. Young women in urban areas face difficulties too but seem to be gaining more in confidence & self-reliance.

Comment:

I feel that this is an important topic and highly relevant to those of us who work here in the Middle East, where arranged marriages are also the norm. It will be interesting to see to what extent, if any, attitudes change in China and whether such change, if it comes, will be reflected here in the Gulf.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)